16 October, 2025

Many organizations treat Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVEs) as first-class citizens. Some even enforce strict service-level agreements (SLAs) for remediation, tied directly to their CVSS severity scores. Modern tools can automatically scan entire codebases and generate a real-time snapshot of an organization’s security posture.

Finally, we have a simple, data-driven way to measure how secure our applications are. The numbers are based on hard and real data. Moreover since attackers have access to the same information, building your entire AppSec strategy around these vulnerability dashboards should make perfect sense… right?

- How much can we really trust CVEs?

- How reliable are CVSS scores in the context of measuring application security risk?

In this blog, I take a closer look at the science behind CVEs and CVSS scoring. Who creates and manages them, how they are assigned, and whether they truly reflect the security risk they claim to measure.

Key takeaways

-

The CVE database contains significant noise. Research shows that up to a third of all listed vulnerabilities are either unconfirmed or disputed.

-

CVSS scores are highly inconsistent. Studies found that more than 40% of CVEs receive different scores when re-evaluated by the same person just nine months later.

-

Building your application security strategy around CVEs and CVSS scores is fundamentally flawed and can lead to misplaced priorities and wasted resources.

Common Vulnerability Enumeration

Common Vulnerability Enumeration (or CVE) is a publicly disclosed cybersecurity vulnerability. CVE is technically a CVE ID, which is a standardized unique identifier for a vulnerability, formatted as CVE-Year-Number.

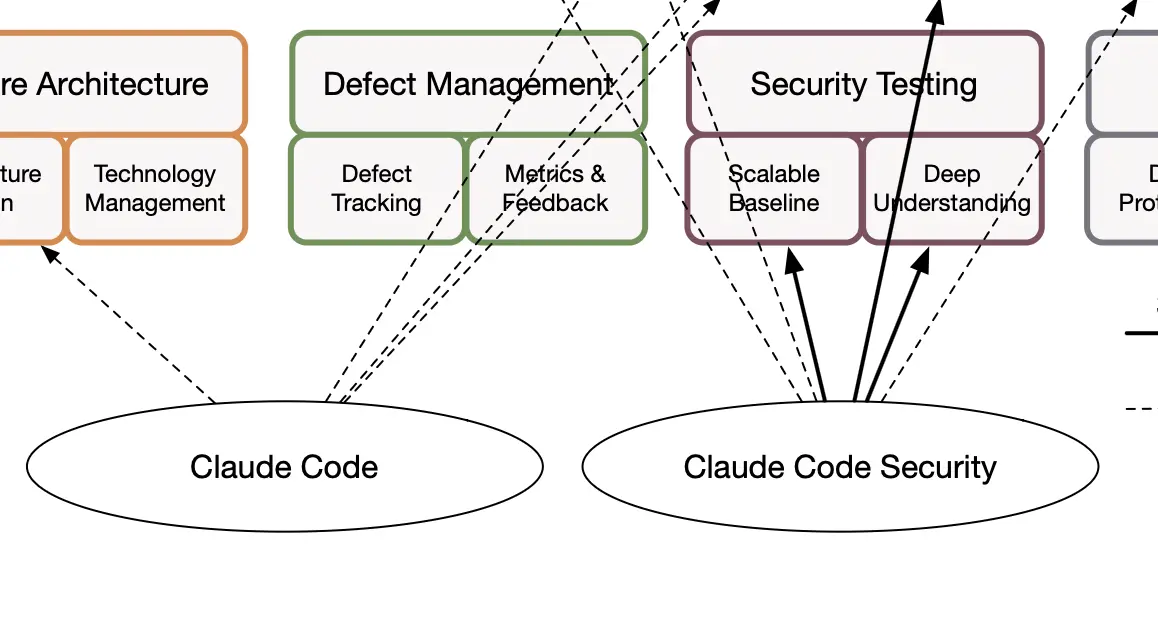

The CVE journey in a nutshell

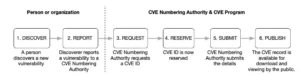

Here is the CVE creation process from its discovery to a final publication in the CVE database.

- A person or an organization discovers a vulnerability.

- The vulnerability is reported to a CVE Numbering Authority (CNA).

- The CNA reviews and verifies the submission, then requests or assigns a CVE ID through the CVE Program. Along with the ID, the CNA creates a preliminary CVE record containing a short description, public information, and references.

- The CVE ID is now reserved. At this stage, only the identifier exists and the detailed information is not yet public.

- Once the vulnerability details are confirmed and documented, the CNA finalizes the record and submits it for publication.

- The CVE is then published, making the details publicly available for downloading and viewing through official databases like the CVE List and NVD.

CVE Numbering Authorities

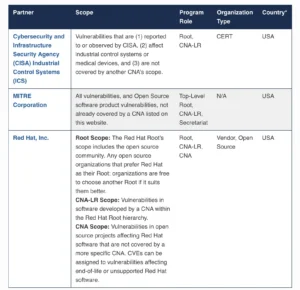

Originally, MITRE created all CVE identifiers themselves. However, in the early 2000s, they launched the first CVE Numbering Authority (CNA) program. The initial CNAs were large corporations such as Microsoft, Oracle, and Red Hat. This allowed them to assign CVE IDs for vulnerabilities found in their own products. Over time, the CNA concept expanded rapidly, and today there are hundreds of CNAs worldwide.

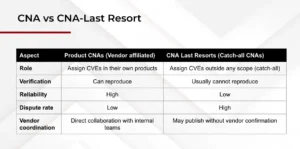

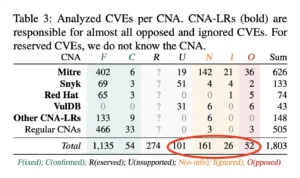

There’s one very important thing to understand about CVE Numbering Authorities. Some CNAs are responsible only for their own products. For example, Microsoft or Oracle act as CNAs for their respective ecosystems. But there’s also a special group called CNA Last Resort (CNA-LR). These act as catch-all CNAs for vulnerabilities in products that don’t have a dedicated CNA. For instance, many vulnerabilities in open-source projects are handled through CNA-LRs.

Vendor CNA vs CNA Last Resort

As you can imagine, the disclosure process differs slightly between a product CNA and a CNA-LR. Product CNAs usually have strong internal processes to reproduce vulnerabilities and assess their impact early on. CNA-LRs, on the other hand, don’t maintain the products themselves, so their ability to validate issues is much more limited. In the next section we will discuss the impact of that.

Overall, the CVE creation and management process is well structured. However, there are still several problems worth discussing. In the next part of this blog, we’ll look at the most important ones.

Key issues with AppSec risk management using CVEs

Many of the problems with CVEs stem from a fundamental misalignment of incentives. Vulnerability researchers often aim to publish as many CVEs as possible to build their reputations. Product CNAs, on the other hand, have little motivation to create CVEs that expose flaws in their own software. Meanwhile, CNA Last Resorts typically lack the technical context for thorough validation and are more inclined to publish quickly rather than accurately. All of this ultimately falls on the developers and maintainers, who must fix these reported issues even when the reports are questionable. To make matters worse, the dispute process is inefficient and rarely used.

Let’s take a closer look at how these factors contribute to the broader challenges within the CVE ecosystem.

Lack of an in-depth CVE validation by CNA Last Resorts

CNA Last Resorts (CNA-LR) are organizations that act as catch-alls for vulnerability reports. They often lack direct knowledge of the affected product and have very little technical context. This creates a natural disconnect between the code owners and the CNA-LRs responsible for deciding whether a report qualifies for a CVE.

Without access to the source code, in-depth verification becomes extremely difficult. CNA-LRs aren’t bad actors, but they tend to err on the side of caution. Failing to assign a CVE for a genuine vulnerability is seen as far worse than creating one for what might simply be a software bug. As a result, their verification standards are typically less strict which contributes to the growing number of CVEs that don’t represent real security issues.

Eagerness to create as many CVEs as possible by vulnerability researchers

For researchers, owning a CVE is prestigious. Academic papers that reference successfully assigned CVEs are often perceived as more credible and impactful. For security professionals, a CVE entry is also a valuable addition to a résumé. This creates a clear motivation to generate more CVEs, even when the impact may be questionable.

Moreover, the system can be gamed and creating a CVE for the sake of it isn’t particularly difficult, especially given the CNA Last Resort’s tendency to publish rather than risk missing a legitimate vulnerability.

A great illustration comes from Florian Hantke, a PhD student from Germany, who decided to test the system. In just a few hours, he managed to create a CVE for a deprecated system that no one actively uses. Despite its irrelevance, the vulnerability was assigned a CVSS score of 9.1 (later downgraded to 7.5). You can find his detailed account in his blog post.

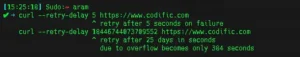

Another well-known example is the questionable curl vulnerability that has received a CVSS score of 9.8 out of 10 (later downgraded to 3.3). Curl is a command-line tool used to communicate with websites or APIs. One of its optional flags allows retries after a delay. If you set that delay to an extremely large value, it may overflow and retry immediately. Technically, that’s a bug, but its security impact is effectively zero.

So you might start wondering at this point, why aren’t developers disputing that? Well, that brings us to the next issue on the list.

Inefficient CVE dispute process

Although formal mechanisms exist to dispute or reject a CVE, they are rarely used. Invalidating incorrect CVEs has historically been difficult and only after significant community backlash did MITRE make the process somewhat feasible. Most maintainers know this and don’t even bother; it’s often cheaper to fix the issue than to fight it. In many cases, MITRE simply marks the CVE as “disputed” and leaves it in the database. The burden of proving that a vulnerability does not exist falls entirely on the maintainer, who must navigate a cumbersome, multi-stage dispute process.

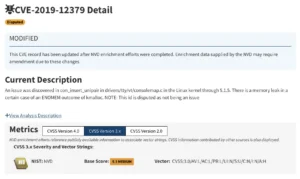

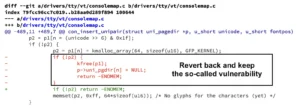

A good example is CVE-2019-12379, which highlights how messy this process can be.

In 2019, a CVE was created for a Linux kernel memory leak. The code owner argued that the issue had no real impact, yet the NVD still assigned it a medium severity score. To resolve the matter, the maintainer released a patch, which unfortunately introduced an actual vulnerability. The patch was later reverted, but the original CVE remains listed as disputed in the database to this day.

Refusal to create a CVE by vendor CNAs

At the same time, product CNAs tend to be less eager to assign CVEs for vulnerabilities in their own software. After all, a CVE is bad publicity. This has created a reverse effect: organizations that act as CNAs for their own products are often reluctant to acknowledge vulnerabilities, even when they are legitimate. This tension led to the creation of notcve.org. NotCVE is a platform where researchers disclose high-impact vulnerabilities that were never recognized by the CVE program. In other words, some real vulnerabilities never make it onto the official CVE list at all.

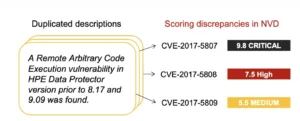

Duplicates and redundancies

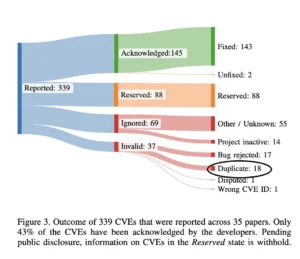

As mentioned earlier, CVE reporters take pride in getting a CVE published — it can have a tangible impact on their careers. This incentive often leads to duplication and redundancy within the CVE database, where multiple CVEs are created for the same underlying issue. According to a scientific study by Schloegel et al, about 5% of the CVEs analyzed were duplicates, highlighting yet another source of noise in the system.

The scale of the CVE problems

So far I have discussed various issues with the CVEs process. The real question, then, is how bad is the problem? In other words, how many CVEs in the public database actually represent real security issues? We all remember the major headlines with Log4J, Heartbleed, Spectre&Meltdown, and other CVEs that caused massive financial and operational damage across industries.

A recent high quality publication by Schoegel et al, examined this issue in depth. Their quantitative analysis found that nearly one-third of the CVEs they studied were either unconfirmed or disputed by the maintainers.

To be fair, their dataset was drawn from other academic studies, not a random sample of all CVEs, so the results can’t be generalized to the entire ecosystem. Nonetheless, if one-third of reported vulnerabilities are unverified, that’s a serious signal.

And here’s the kicker: most of those problematic entries originated from CNAs Last Resort!

CVE realities: key takeaways

- The CVE Program maintainers should focus on improving the quality control and oversight of their CNA-LRs.

- CVE Program maintainers should make the dispute process more accessible.

- As a user of CVEs – whether for dashboards, prioritization, or risk modeling – be mindful of where the data originates. When assessing real-world impact, it’s often wiser to prioritize CVEs issued by product vendors rather than those created by CNA-LRs.

Common Vulnerability Scoring System

So far, we’ve looked at the potential noise within the CVE database. Unfortunately, that’s only part of the problem. Things get even more complicated once we bring severity scoring into the picture.

Let’s briefly revisit the journey of a vulnerability from discovery to becoming a published CVE. The process starts with the reporter, then moves through a CVE Numbering Authority (CNA), which ultimately publishes the CVE. But the story doesn’t end there. After publication, NIST reviews the CVE and assigns a severity score using the CVSS framework.

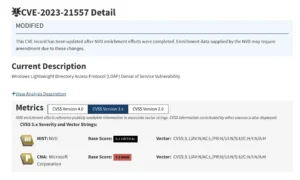

Note that NIST isn’t the only authority adding a CVSS score. Some CNAs may also assign their own CVSS score. Here’s an example: a single CVE can have two independent and different severity scores, one from Microsoft and another from NIST.

That might seem strange, but before diving into the details and differences, let’s first look what CVSS actually is and how these scores are calculated.

What is CVSS and why do we need it

CVSS stands for Common Vulnerability Scoring System. It’s the industry-standard framework for assigning severity scores to CVEs. The idea behind CVSS is sound: when you’re dealing with thousands of vulnerabilities, a consistent scoring system helps you compare impact and prioritize remediation.

The National Vulnerability Database (NVD) provides CVSS scores for all CVEs, although, as mentioned earlier, it’s not the only authority that does so.

Over the years, several versions of CVSS have been released. The most widely used today is version 3.1, while version 4.0 is the newest iteration. It addresses some of the shortcomings of 3.1, but so far NIST isn’t ready for version 4.0.

How to calculate CVSS

A CVSS score is essentially a vector of metrics, each derived from an ordinal scale. Ordinal scales rank values but don’t express the magnitude of difference between them.

Take the Attack Complexity metric, for example. It can be either Low or High. While High clearly means the attack is more difficult, the scale doesn’t tell us how much more difficult. It’s not as if a High-complexity attack is ten times harder than a Low-complexity one — the scale simply establishes order, not distance.

The CVSS calculator itself is quite straightforward: you select values for a set of predefined metrics, and the system computes the overall score.

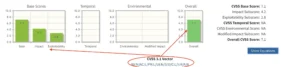

It’s also worth noting that the CVSS 3.1 has 3 dimensions for scoring: Base, Temporal and Environmental Score metrics. NIST publishes only the Base Score. The other two are left for organizations to determine on their own, since NIST doesn’t have the contextual knowledge to calculate them accurately.

Key issues with AppSec risk management using CVSS

Translating the vector into a numeric value

A CVSS score is essentially a vector of base metrics, all of which are ordinal. NIST developed a heuristic formula to combine these values into a single number on a scale from 0 to 10. From a measurement theory perspective, however, this approach is fundamentally flawed. Ordinal scales can’t be combined mathematically in a valid way.

Still, as a heuristic, it serves a practical purpose. Without it, the CVSS score would be much harder to interpret or communicate, since working directly with vector scores isn’t convenient for most users. Hence, on its own, that simplification isn’t catastrophic. But the real problems begin when tools and organizations start performing mathematical operations on top of CVSS scores. Many Application Security Posture Management (ASPM) tools, for example, define a “risk score” using formulas such as:

Risk = Average (CVSS × (1 + EPSS) × (1 + IsProduction)),

where EPSS a predicted likelihood score, IsProduction is 0 or 1 depending on whether the asset is in production.

These aggregated risk models are scientifically unsound, because none of the underlying operations (multiplication, averaging, or addition) have a valid statistical basis when applied to ordinal data. The result may look quantitative, but it lacks any real measurement meaning.

CVSS scores are unreliable and inconsistent

A more serious issue lies in the consistency of CVSS scoring. Many of the base metrics are open to interpretation. You might consider an Attack Complexity to be Low, while I might classify it as High.

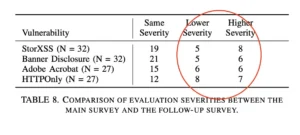

Research has shown that evaluators often disagree on how to score the same vulnerability. Even more concerning, the same studies found that the same evaluator can assign different CVSS scores to the same vulnerability when re-evaluated just nine months later.

And in some cases, the inconsistencies become absurd. Here is an example where a single vulnerability was duplicated in the CVE database. Moreover it has received three different CVE IDs, each with wildly different CVSS scores.

But why is this happening? How hard can it be to score a CVE using a simple calculator?

Context dependency and threat model

It turns out that not only the temporal and environmental metrics, but even the base metrics in the CVSS vector are highly context-dependent. Evaluators need a solid understanding of how the affected application actually works to assign scores accurately.

An empirical study found that a number of those base metrics, i.e., User Interaction, Attack Vector, Scope, and Privileges Required, are often difficult to score consistently, largely because evaluators lack sufficient application context.

CVSS score inconsistency on average

Although I’ve highlighted several issues with CVSS scoring, I tend to agree with the saying: “CVSS is like democracy – the worst system available, except for all the others ever tried.”.

In practice, I believe that CVSS scores generally work reasonably well. Most studies show that while evaluators may disagree on specific scores, the variations are usually minor. The examples I’ve presented here are, thankfully, exceptions rather than the rule.

A more serious issue that is persistent in the industry is using CVSS as a measure of risk.

CVSS is a not a measure of risk

In a simple form, risk is expressed as:

Risk = Likelihood x Impact

The CVSS score, however, captures only the impact of a vulnerability, not its likelihood of being exploited. Treating impact alone as a proxy for risk is therefore a fundamental mistake. Because even basic probability tells us that if the likelihood of exploitation is zero, the resulting risk is also zero, regardless of how severe the potential impact might be.

In other words, a vulnerability with a CVSS score of 10 could represent no practical risk at all if it exists in a context where exploitation is impossible — for example, if the vulnerable component isn’t exposed, is properly sandboxed, or is protected by compensating controls.

Conversely, a vulnerability with a modest CVSS score could pose high actual risk if it’s easily exploitable, present in critical infrastructure, or has public exploits circulating.

CVSS helps you estimate potential damage, but risk assessment requires understanding both the technical and contextual likelihood of that damage occurring. Confusing the two leads to wasted effort, poor prioritization, and a false sense of security.

Connecting the Dots

Scientific studies show that a substantial portion of vulnerabilities in the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) database are never confirmed or are even disputed. This means that known vulnerabilities, as represented by their CVEs, contain a certain level of noise.

We also looked at the CVSS scoring system, which supports prioritization. CVSS scores are mathematically flawed, and quantitative research has shown that evaluators often disagree. More strikingly, over 40% of vulnerabilities were scored differently by the same expert after nine months. Most importantly though, CVSS measures only impact, not likelihood, so CVE-based prioritization requires context from application owners.

So, what does this mean for managing application security risk?

- Treat CVEs as signals, not absolute truths. Check who issued them. Vendor CNAs are generally more reliable than CNA-LRs, and their scores are likely more accurate.

- Second, rethink CVSS-based prioritization. Consider complementary metrics like KEV and EPSS, which account for likelihood. Combine CVSS data with threat intelligence and asset criticality, and introduce a structured triage process.

Finally, a strong application security program starts with a shared understanding of risk. It emphasizes threat modeling and practical triage, ensuring your team knows how much trust to place in vulnerability dashboards and when to look beyond them.

References

In this section, I provide a list of references. While some of them are blogs articles, many others are A-level quantitative scientific publications demonstrating the level of rigor and depth.

- Confusing Value with Enumeration: Studying the Use of CVEs in Academia. Moritz Schloegel, Daniel Klischies, Simon Koch, David Klein, Lukas Gerlach, Malte Wessels, Leon Trampert, Martin Johns, Mathy Vanhoef, Michael Schwarz, Thorsten Holz, Jo Van Bulck. In Proceedings of the 34th USENIX Security Symposium, 2025.

- SoK: Prudent Evaluation Practices for Fuzzing. Moritz Schloegel, Nils Bars, Nico Schiller, Lukas Bernhard, Tobias Scharnowski, Addison Crump, Arash Ale-Ebrahim, Nicolai Bissantz, Marius Muench, and Thorsten Holz in IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (S&P), 2024.

- Shedding Light on CVSS Scoring Inconsistencies: A User-Centric Study on Evaluating Widespread Security Vulnerabilities. Julia Wunder, Andreas Kurtz, Christian Eichenmüller, Freya Gassmann and Zinaida Benenson. In 2024 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP).

- https://lwn.net/Articles/944209/

- https://lwn.net/Articles/801157/

- https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/kernel-recipes-2019-cves-are-dead-long-live-the-cve/176707403#12

- https://infosecwriteups.com/how-to-get-cves-online-fast-c0d6d897c04d

- https://daniel.haxx.se/blog/2023/08/26/cve-2020-19909-is-everything-that-is-wrong-with-cves/